Different managers want to create different styles of attacks. Some favour isolating wingers, others want to fashion transitional attacks into space. Some want to overload wide areas to draw teams out and attack the subsequently underloaded centre, others favour retaining numbers in the middle at all points.

Michael Beale’s philosophy is based around working central overloads, getting his creators on the ball in the pockets and playing in combination with one another. And, because all styles of play have a guiding light, other principles are based on achieving this core aim.

And yet, while creating wide attacks is not the focus, the wide areas are still important both directly and indirectly as low blocks are constantly faced domestically. Rangers have been accused of “lacking width” repeatedly this season, but it’s perhaps more accurate to suggest that they’ve lacked threat from their width as opposed to lacking players stationed by each touchline.

On Wednesday night, however, in a 4-0 win over Livingston, Beale’s men looked slicker in possession, their rotations variable and occupation of the wide areas visibly more threatening. Here’s what changed…

Why do full-backs play high and wide for Beale? To facilitate his attackers playing in central areas, more valuable in statistical terms, closer together and closer to goal.

“The key thing is for the full-backs to provide the width so we can overload the middle, that’s where the goal came from at the weekend,” he explained on Wednesday night in response to Marvin Bartley’s question on Viaplay about individual responsibility in the final third.

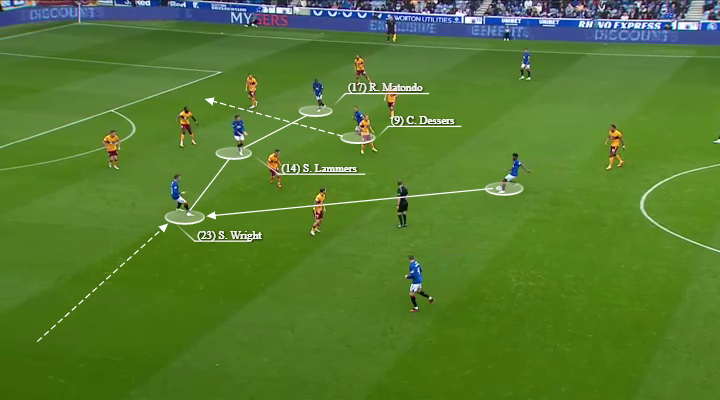

You can see in the strike against Motherwell that three attackers, Rabbi Matondo, Sam Lammers and Scott Wright (who’d made his way over from the left) are narrow between the lines, able to combine close to goal with two full-backs stationed wide. So why has this type of fluency been a rarity, both on Sunday and overall this season?

Beale continued: “The thing is, there’s a lot of players who’ve left or are not available tonight [in the final third]. We all know if you get the ball in the final third you’re looking for players to go and make things happen. It’s completely new relationships and I get everyone wants it to just click.”

Last season with a settled starting 11, players who knew the style and each other, winning run-of-the-mill matches was not an issue, in fact, it became a strength. Where Beale couldn’t get over the line was in big games - an accusation defeat in September’s Old Firm has not helped.

For the attacking freedom Beale hands his players in the final third to work these “relationships” need to click and with so many changes overall, that’s rarely happened. What’s more with a Todd Cantwell injury, Lammers still finding his feet and the loss of Ryan Kent and Fashion Sakala, who offered dynamism and variation moving into the wide areas last season, too often the wings haven’t carried the direct and indirect attacking threat required.

Beale looks to get the best out of his attacking players and remain unpredictable as a team by offering them positional freedom. Providing structure to access the final third and stay there, but also entrusting his creators to maximise the autonomy they’re then granted.

“I’m really glad that the coach gives the attackers the freedom to do what we want to do,” Danilo said earlier this summer.

“I’m enjoying myself, I said when I came here the manager is going to give me the freedom to play the way I want to and I think you’re starting to see that because I’m picking up the ball in lots of places,” Cantwell commented last season.

“[Beale] loves attacking players, who can switch positions and don’t stay in the same place,” Lammers said at his unveiling press conference.

Whether it be a No.10's interpretation of space in a free role, or a winger in a more positionally-static team taking advantage of a one-on-one situation. All managers are trying to create their own interpretation of optimal attacking situations for their best final-third players.

As Beale once commented: “Utopia for me is finding a group of players that have freedom to rotate in the final third,”

We’ve perhaps established some of the reasons why Rangers have lacked fluidity this season, according to Beale. So what changed on Wednesday?

The manager was asked in his post-match press conference whether there’d been a “change in philosophy” since the start of the season given the greater threat from wide areas.

“The biggest issue we’ve had is the players who knew how we played in the final third moved on,” he said in reply.

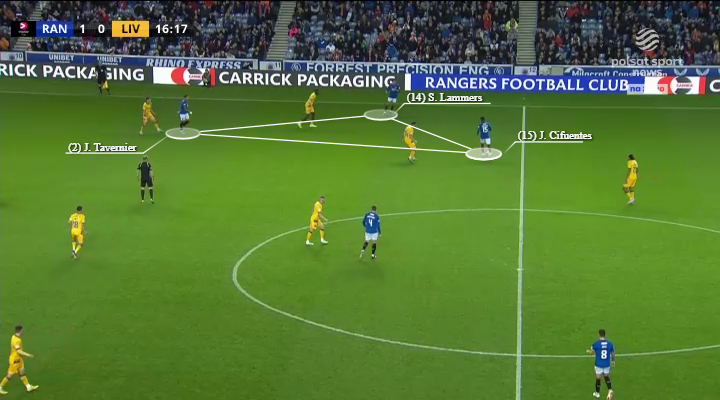

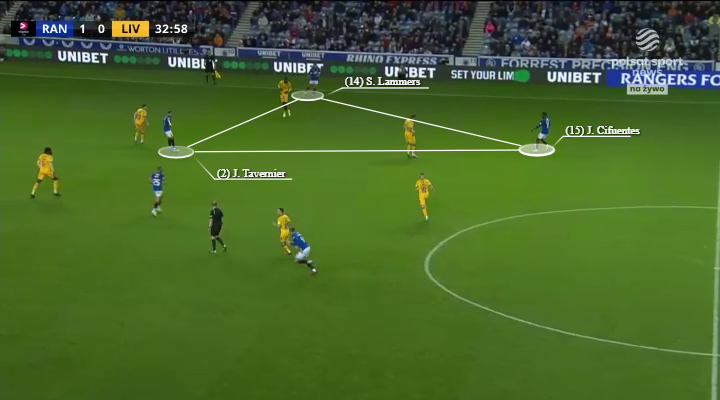

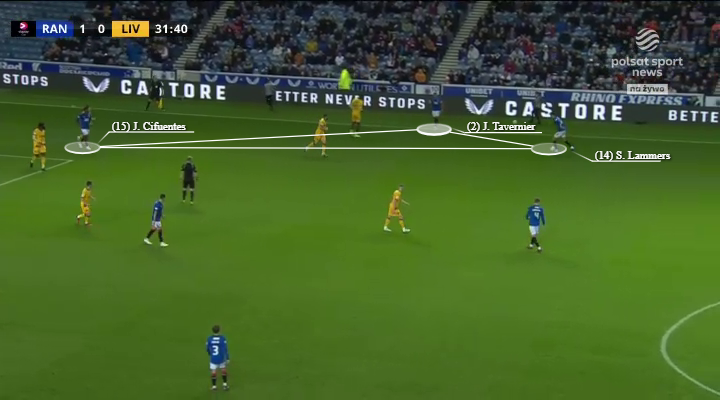

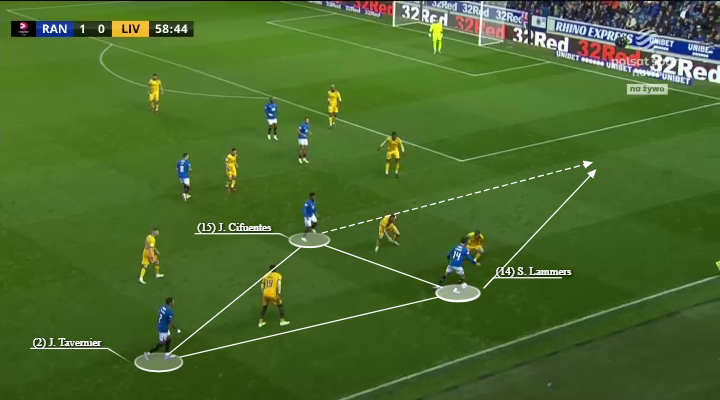

“We want back to the 4-3-2-1 tonight and asked them to play a little wider depending on the triangles how we always have. I was pleased enough, the triangles on either side worked well. I thought Cifu went high and let Sam [Lammers] stay wider, other times James [Tavernier] came inside. Ridvan and Abdallah between them the energy they showed led to the first two goals, the left side probably won us the game.”

Intrestingly when asked about the wide triangles on either side Beale’s language was not one of instruction. The terms used were general and clearly, improvement was heavily based upon players’ interpretation of roles and better-functioning relationships, understanding what was required to create opportunities in specific situations against a set defence.

What did it look like in practice? Rotations in the wide triangle offered variation on the right and on the other flank the inclusion of a different profile in Ridvan Yilmaz, and a clearly more settled player in Sima, also provided differing threats.

READ MORE: Jim Forrest: Remembering Rangers' 57-goal season forward

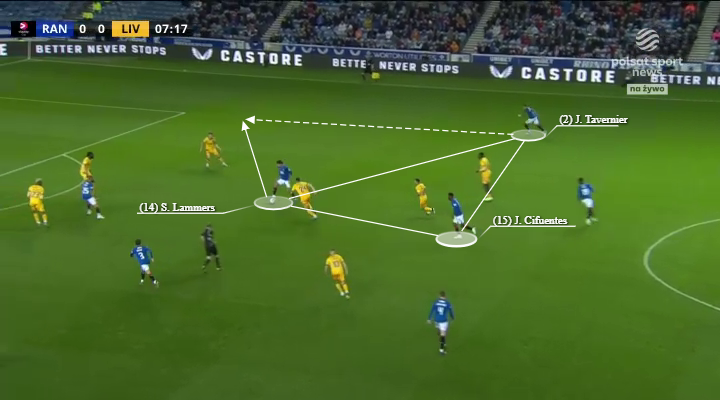

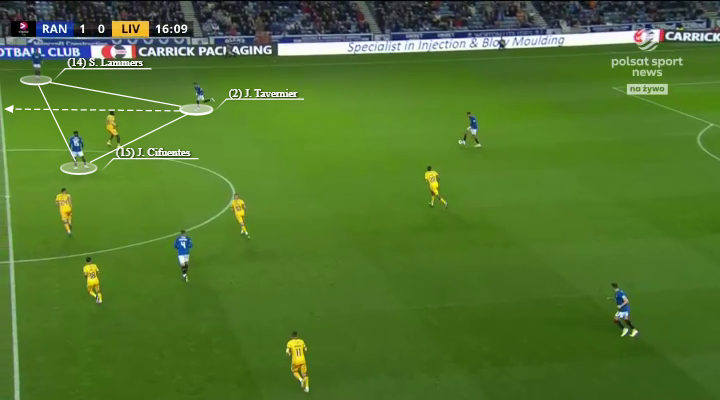

Lammers, Cifuentes and Tavernier posed a range of threats for David Martindale. Mixing up who occupied the width, depth and top of a right triangle.

If, for example, Tavernier was wide on the last line providing a final-ball threat out wide, Cifuentes was situated deep and able to play forward passes from his favoured right half-space at the bottom of the triangle, Lammers could occupy the top and twist and turn either way in the pocket.

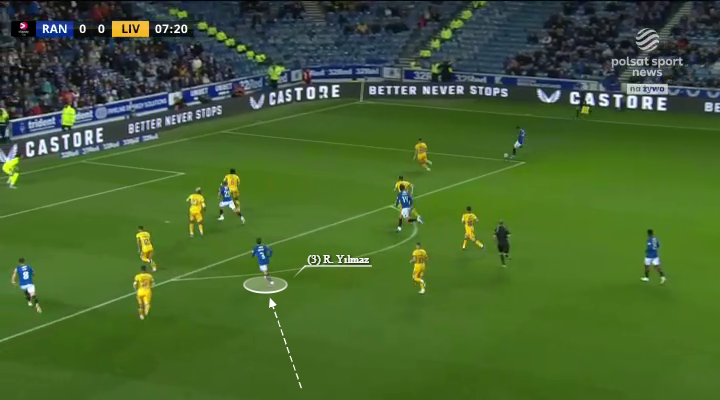

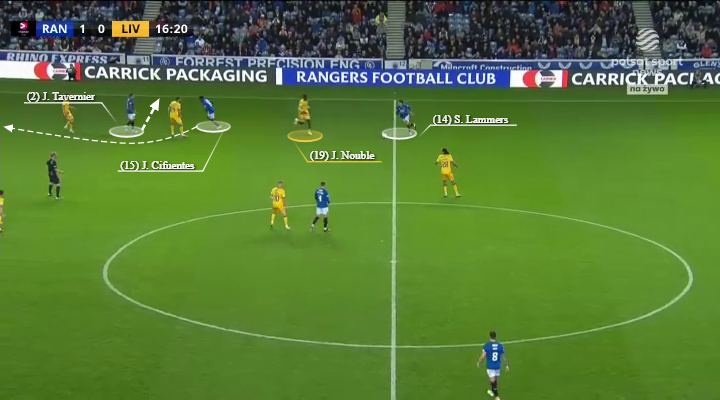

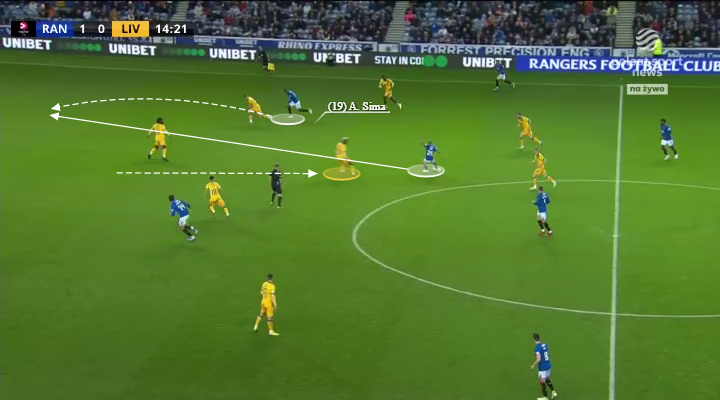

Notice the narrow positioning of Ridvan as the home side plays vertically to cut through Livingston here.

Whereas if it was Lammers stationed by the right touchline providing width, Tavernier could interpret the top of the triangle in different ways. Instead either providing a box presence or, if moving from deeper areas, making vertical underlapping runs through the pitch. There was a notably better tempo about the home side’s play throughout - moving the ball quickly across the pitch before Livingston could recover numerically.

On other occasions, Lammers recognised it was his turn to drop to the base and provide depth. Here interchang with Cifuentes and, having isolated himself against Nouble, skipping beyond before sliding through Roofe. This time, notice it’s Sima who’s overloading from the left alongside the striker.

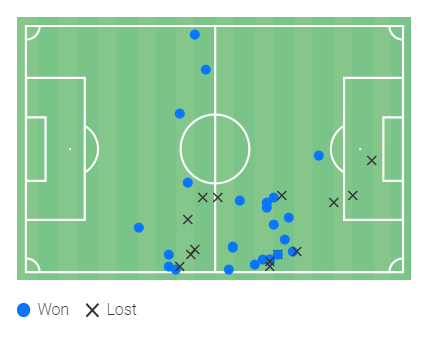

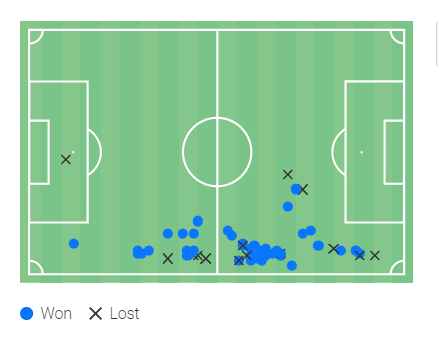

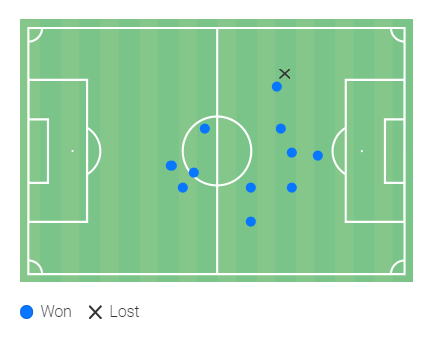

Lammers' touch map is shown below. The 26-year-old was so often getting on the ball in these wide areas, facing play and able to drive forward.

He completed five of seven dribbles in the game and given his superb one-on-one skillset and two-footed ability, provides an interesting threat in these positions. Able to often isolate himself against a forward in Nouble, cut inside against the Livingston press angled to the touchline and open up a greater array of passing angles paying on his weak foot. What’s more, this type of vertical movement from the flanks attracts defenders forward to confront and adapt their body shape.

On other occasions, it was Cifuentes who made the underlapping runs through the pitch while Tavernier stayed deep.

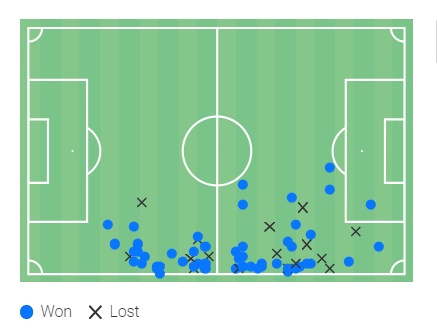

Comparing Tavernier’s touch map from the weekend’s game against Motherwell (top) to the Livingston game (bottom), his increased involvement inside the pitch was obvious.

All three players on the right, Cifuentes, Lammers and Tavernier, are capable in all three zones but offered different threats when occupying them. Livingston would have to defend Lammers by the touchline and Tavernier at the top of the triangle differently to the contrary.

READ MORE: Inside Sam Lammers' PSV rise and his unique two-footed skill

The left-hand side was less variable than it may have been if, for example, Nico Raskin, Kieran Dowell or Todd Cantwell occupied the left-sided midfield slot and Rabbi Matondo, more comfortable driving forward from the touchline, made up the wide triangle with Ridvan. The Turkish left-back is a more progressive profile in general, able to play forward quickly or, as evidenced by his superb strike, progress up the pitch by carrying.

WHAT. A. GOAL! 😱🔵

— Viaplay Sports UK (@ViaplaySportsUK) September 27, 2023

Rıdvan Yılmaz carries the ball from his own half and produces a fine finish 👏#ViaplayCup | @spfl | @RangersFC pic.twitter.com/iA9HGETkIj

That’s not to take anything away from Sima who was excellent. His running onto the ball, as opposed to attacking players with the ball like Matondo, made the Livingston defence uncomfortable and took defenders where they didn’t want to go. The players contrasting styles and “energy” provided a different form of variation.

Sima gives @RangersFC the lead 🔵

— Viaplay Sports UK (@ViaplaySportsUK) September 27, 2023

The Senegalese forwards finds the back of the net with a fine placed finish 👏#ViaplayCup | @spfl pic.twitter.com/oaQfj5QkEL

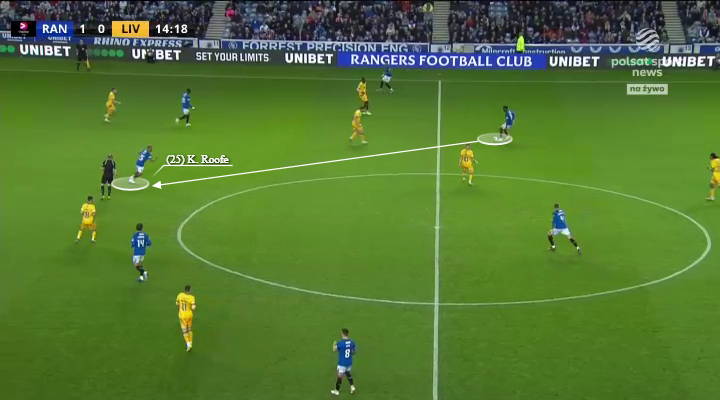

Both sides were also helped by the first-half inclusion of Kemar Roofe. Look how deep he was to drop and offer an extra passing option in midfield, often with his arms up conducting play and spinning to provide the odd through-ball.

When Beale said his team went back “to the old way” the role of an involved forward, dropping to pull the defence out of shape, with a pacey goal-threat like Sima running beyond proved crucial.

Beale commented afterwards that the “energy and directness on the left won the game” and it was the source of Rangers’ first three goals.

Equally on the right, the relationships he speaks of so often looked in better shape to use the wide zones in a more threatening manner.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here